In this article, PadSplit CEO Atticus LeBlanc challenges the notion that solving the housing crisis requires a missionary-like dedication, arguing instead that it can be a profitable venture for property owners. He emphasizes that by repurposing existing single-family homes into affordable shared housing units, property owners can not only contribute to addressing housing shortages but also generate attractive returns on their investments.

Contrary to popular belief, I don’t believe you have to be a missionary to make an impact on affordable housing. Instead, I’ve long held the notion it’s better to be a “misfit.”

One of our earliest investors, Arjan Schütte, introduced me to the idea of “misfits.” Arjan and his impact-driven investment firm, Core Innovation Capital, respect both shrewd mercenaries and the most devout missionaries but typically invest in neither. Instead, the fund focuses on “misfits,” which they describe as a “strange alchemy between the two.” Neither missionary nor mercenary, but somewhere in between, a misfit is a person driving toward positive social impact while accepting the market realities of creating a sustainable endeavor. Core’s results in supporting misfits are hard to deny. After making a commitment at the Clinton Global Initiative in 2009 to create $6B in financial empowerment for the underbanked, Core’s portfolio companies have actually delivered > $60B across more than 16.7M underserved individuals.

Unfortunately, many advocates of affordable housing dismiss the idea that for-profit solutions have a role to play in solving our current crisis. The cause of the crisis under this view is not the lack of housing supply or the regulatory barriers to increasing it, but rather the greed of evil developers and investors. These well-intentioned advocates tout non-profit or government-based solutions instead, expecting either taxpayer-funded subsidies or charitable donations to solve the massive gap in our affordable housing market. But this philosophy misses the mark by focusing on intentions rather than results.

Let me be clear — I’m in favor of any and all scalable solutions, including those fostered by non-profits or governments. But to rely solely on these approaches ignores both factual realities and human behavior.

I prefer a more pragmatic approach.

As an observer of the current political division in our country, it’s hard to take seriously any solution that relies on a coordinated and well-funded federal approach to housing, regardless of the ambitious proposals recently offered by President Biden in his State of the Union address. I don’t have specific critiques of those proposals, but in case you missed it, our congressional leaders only just barely avoided another government shutdown last week with hours to spare. We’re also in the middle of a presidential election year with spiraling national debt; the HUD secretary just announced her resignation; and both chambers are deeply divided (perhaps a gross understatement). Many of the proposals offered in the State of the Union would be ambitious even if the President had control over both the House and Senate, which he does not. But our housing and homelessness crisis is in dire straits right now, and we have the opportunity to address it right now, even without government intervention.

Making existing housing more efficient

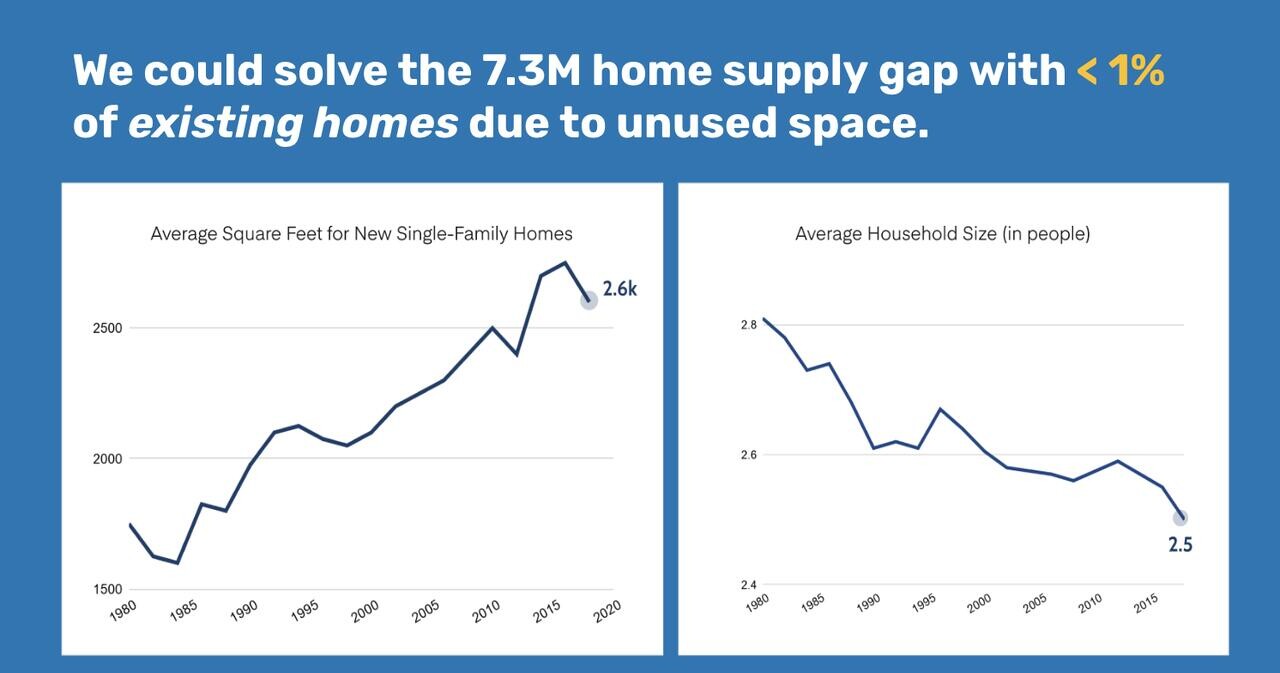

Household sizes have declined since the first census of 1790, from 5.79 persons per household to 2.50 persons per household in 2022. Yet the sizes of homes in the U.S. have been steadily increasing since before 1960. In other words, the U.S. has been getting less and less efficient in the way we house ourselves during the last 65 years. Today, the largest segment of American households are single persons, living alone, at 28.6% of the total. If you count single adults sharing space the number climbs to 39.6%, and 74% of all households do not have children.

Despite these trends, only 13.8% of our housing stock is comprised of studios or one-bedroom apartments. The combined factors of larger single-family homes with the shrinking household makeup have created a huge mismatch.

What it has left us with is a tremendous amount of wasted or underutilized housing at a time when we have a shortage of 7.3 million affordable homes, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. If you take the total square footage of housing that exists today in the U.S., 225 billion square feet, divided by our total population, you will find that we have more housing square footage per capita than at any point in American history. Today, the average allocation of residential square footage in the U.S. is 887sf per person. However, using the same per capita square footage efficiency from 1950 (298sf) or PadSplit’s spatial efficiency across our 11,000 units, you would find that only 1% of the existing housing square footage in the U.S. would suffice for 7.3 million x 1 person households!

No new construction, no further expansion into the exurbs, no massive environmental costs… just allocate the empty housing for people to live in without touching 99% of the existing housing in the U.S.

To be fair, the 7.3M unit gap includes more than just single-person households, but even making allowances for an average household size of 2.5 persons, you’re still talking about less than 2.5% of already existing housing.

This creates an undeniable opportunity for a fast, effective, and extremely cost-efficient solution to address affordable housing, which brings us back to the missionary question. At a recent presentation for an audience of 150 people, I laid out the facts above. I then asked to see how many missionaries in the crowd would be willing to house a stranger in their personal residence. Only one hand was raised, and she later told me that she had been renting a room in her home to help cover the mortgage. I suspect if you ask yourself the same question, you will likely treat the possibility with similar reticence as the rest of the audience.

When I asked the same audience how many people were interested in earning a better return on their investments, nearly everyone in the room raised their hands. For anyone who believes that profit has no place in affordable housing, I beg the same question or questions of you.

Now if I offered to pay you $240,000 to house a stranger in your home, half the average cost of an affordable unit built in CA, would you change your response?

My company, PadSplit, has only been able to create 11k affordable units because we’ve demonstrated that our model can improve the return on housing investment. If it wasn’t more profitable, there would be no incentive for our hosts to participate.

I would also ask what percentage of U.S. housing stock has been built by either a non-profit entity, a public entity, or an academic expert. Or whether your home has been built by either a non-profit or public entity. If we’re going to address our housing shortage, we need to start looking at ourselves rather than at outside parties or governments.

Bottom line: We need solutions now.

Government programs like the low-income housing tax credit have been extremely successful, creating more than 3.3 million homes over the last three decades, and Housing Choice vouchers have been an amazing tool for helping low-income households afford homes.

But we need 7.3 million more affordable units right now. The Low-income Housing Tax Credit program only works because the participants, i.e. developers, can earn a profit from creating these housing units. Housing Choice vouchers only work so long as the housing providers continue to get paid market rents or higher. No enterprise, non-profit or otherwise, can be sustainable without ongoing sources of revenue or by losing capital every year.

If we are serious about solving this problem anytime soon, we need to embrace a philosophy of incentive alignment. Creating affordable housing should be an attractive investment so that more people participate. I have had the great privilege of seeing the positive impacts that are possible from a system of aligning incentives between renters in need of better options and housing providers seeking better investment returns.

Frankly, making affordable housing a good investment is the lesson we should have learned from LIHTC and Housing Choice that seems to have been lost in the current public mindset. The same lesson has been proven again recently in Los Angeles with Executive Directive No. 1 enacted in December 2022. The directive dramatically streamlined zoning and permit approvals for housing projects that were 100% affordable while allowing any applicable density bonuses. City departments were ordered to process approvals on building plans within 60 days and to process clearances for building permit applications and certificates of occupancy within five days. Developers who previously had no interest in affordable housing suddenly changed course. According to the LA Daily News, the number of permitted affordable housing units in the 12+ months since the directive was 16,150, which is more than 2020, 2021, and 2022 combined!

Developer Terry Harris, who is currently leveraging the program for a 7-story, 100% affordable apartment complex, revealed his mercenary roots when he was quoted as saying, “I’m just trying to be as greedy as possible.”

I have to imagine (and hope) that quote was made in jest, but it illustrates the point that housing creation is still a business of incentives, and if we want more housing units and greater participation, we have to first create those incentives. The only reason we have an affordable housing deficit today is because the incentives to create it over the last 50 years have been insufficient relative to the risks. Doing a public good shouldn’t come at a financial loss; we clearly don’t have enough missionaries to fix our housing problems.

Originally published in Atticus LeBlanc’s LinkedIn newsletter, One Room at a Time.